I originally wrote this essay for Uni. I'm not sure why I decide this was worth posting, maybe because it is so short I didn't get the chance to really dislike it, or maybe because a personal website seems the natural home for games crit. Either way you should play Kentucky Route Zero if you haven't yet!

‘Un Pueblo de Nada’ functions as an elegy, if not for the people, though one can never be sure in this game, than for the community that forms the WEVP-TV station. ‘Un Pueblo de Nada’ is an interstitial game for Kentucky Route Zero originally released on January 25th 2018 between Acts IV and V. In it you play as Emily the producer of the aforementioned station, as she handles what will be the final broadcast, lining up tapes and segments and, crucially, observing everything that is going on. Observation, as I will go on to argue, is the key interaction for the player in this game. Though there are other forms of interaction, the player can read and progress along dialogue trees, the player doesn’t react to them in quite the same way.

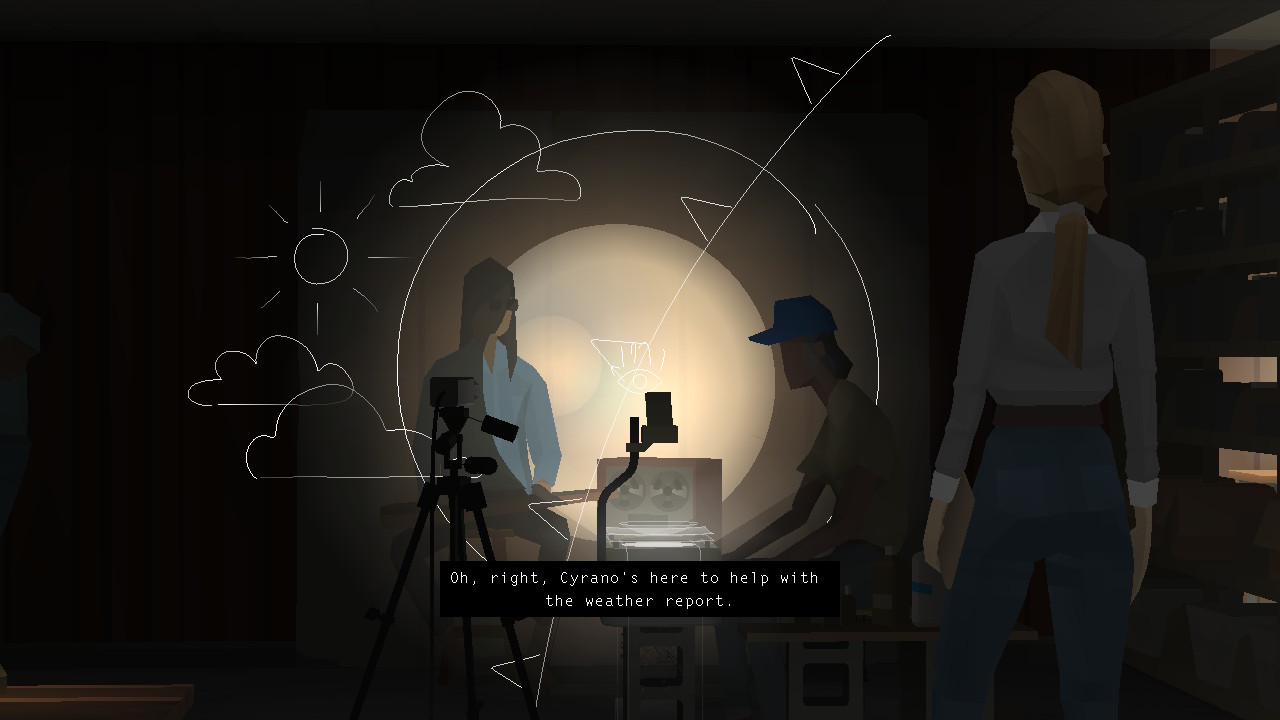

The first image presented in the game is that of rain, pouring through a thin strip of a glass on the entrance door. (figure 1) It is accompanied by the sounds of wind and striking water which, though muted compared to what they will become, are nonetheless erratic. There are lines of dialogue in previous acts that would more explicitly confirm it but the centrality of this shot makes it clear, the storm is inevitable. The camera pans back as the lights fade in and Maya, the interviewee of the evening’s show, steps through the door. This immediately draws a separation between the two spaces, the harsh storm and the station, and establishes the space as a respite. Though Emily’s feelings about the place are ultimately more complex and ambivalent than this, it begins a process of endearment to the space that is carried forward with the game’s precise staging of objects and here is where the player takes control. They may look around the room selecting various objects or people to learn a little about them. Drawings representing Emily’s emotional connections, or immediate associations on appear superimposed top. One example of this is the sun, clouds and standard pressure lines that accompany the weather report station. It provides a familiarity to what will be a decidedly non-standard weather report that conveys a smoothing of difference for Emily. (figure 2) They are functionally the same. There is too a deeper history implied with the presence of the image processor, Emily referring to an engineer who is not present, ‘James,’ whose influence persists into the present moment. Beyond even the interactable objects there is an attention to detail made in modelling of the crooked blinds, the cinderblock tables, the camera, the lights, the microphones, and all the cable that connect them, that combine with all the previous elements mentioned to produce a functioning and lived in place. For the player, this invests them in the location and heightens the effect of its eventual loss.

As Grace Benfell writes in At Home with the Ghosts: Kentucky Route Zero’s Reworking of Capitalist Space ‘The workers that make these spaces mark them, in ways both ethereal and permanent.’ They function against what she describes as ‘non-places,’ a term defined by Marc Augé as a ‘space which cannot be defined as relational or historical or concerned with identity will be a non-place.’ The space is intentionally fragile, funded only by court-order by the Consolidated Power Co., the omnipresent corporation that pervades the game and is monetarily linked to each character. Emily states that ‘so much of archiving is just playing hide-and seek with the weather,’ and this can be mirrored into the station as a whole. The Power company doesn’t pay to maintain the space, it is designed to be ephemeral because, to them, it doesn’t matter. The storm is inevitable because there was never any intention of protecting against it and the people of the station can only fill as best they can.

Kentucky Route Zero is a game infatuated with ghosts and it is a theme that reoccurs often in criticism. Jessica Conditt in their piece, This is the end of 'Kentucky Route Zero,' writes ‘Kentucky Route Zero is a game about ghosts. Fading memories, deserted boomtowns, dead friends, lost family members, unfinished projects, unkillable habits, unknowable truths.’ As Emily states in the game, ‘I guess there are good ghosts and bad ghosts. Like spiders – good in the garden, bad in the shower. The complexity of the multiple definitions presented here are explored directly in Un Pueblo de Nada, where the topic of ghosts is tackled and addressed by the characters in dialogue. Initiated by the imminent presence of the resident ghost, Weaver, that occasionally commandeers the signal of the station, Emily and Elmo begin the discussion. In response to Emily asking if a ghost can only appear when you die, Elmo states ‘Well, that’s one way to do it. But have you ever missed someone so bad you felt like they were haunting you? Or been in relationship with someone where it feels like their ex-lover is always in the room.’ It is a definition that relinquishes the states of life and death and defines a ghost more as effect produced, whether emotional or physical by something that isn’t there. I think this is a useful expression in helping define the player subject relationship within ‘Un Pueblo de Nada.’

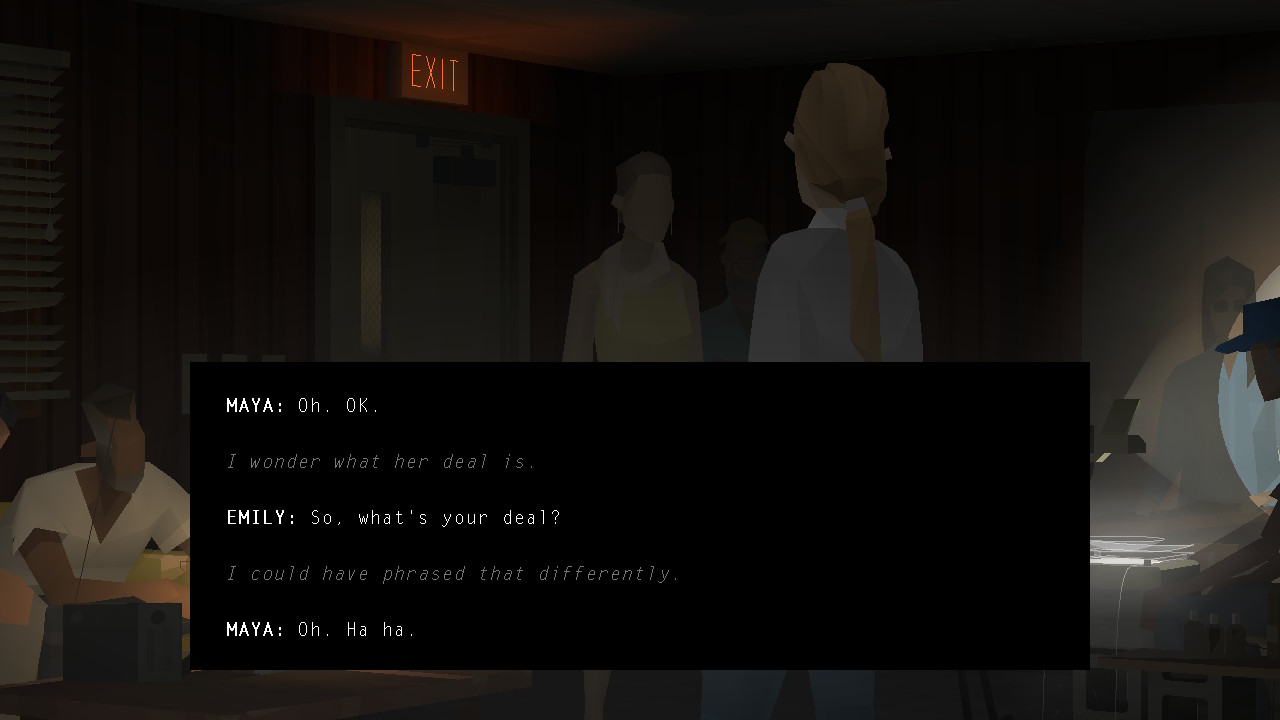

The player is situated in an abstracted space in comparison to their subject of control, Emily. Control exercised by selection rather than direct input is standard in the point-and-click lineage but beyond this the player is still subtlety shifted from control. Advancing through dialogue trees involves selecting Emily’s thoughts rather than her speech. A humorous manifestation of this disconnect is found in Emily’s introductory conversation with the selection of the thought ‘I wonder want her deal is,’ This translate to, ‘So, what’s your deal,’ a curt and clumsy phrase that Emily thinks she ‘could have phrased differently.’ (figure 3) It highlights a perceptive difference between the player character and the player, the player cannot predict Emily’s response, and, the words Emily speaks, influenced by the player, also cannot be predicted. The consequences must be experienced by her in her physical space.

This perceptual difference is further demonstrated by the game’s utilisation of the human voice. Voiced speech is a rare occurrence across the entirety of Kentucky Route Zero, the most notable examples being various songs presented beyond the frame of regular dialogue. This means voiced dialogue is already set up to appear unique in ‘Un Pueblo de Nada.’ There are two main instances of the human voice, the fragments that pierce the static of Ben and Bob’s radio and the voice of the caller in the evening broadcast. Both are shifted towards sound rather than modes of communication. The radio of course because full sentences or even singular words are difficult to make out, tending towards the musical experience of a noise album. And the caller in the exaggerated pauses and stutters that far exceed the reported speech (figure 4). Robert Yang in Video killed the video star: on ‘Un Pueblo de Nada’ by Cardboard Computer writes ‘Even the actor for the radio caller Geoff, Drew Ackerman, runs an actual podcast called ‘Sleep With Me’ where he tells long rambling stories intended to put you to sleep.’ This intertextual reference alongside the fact a character in the game Ron does physically fall asleep reveals the function of this speech as a form of ambient noise.

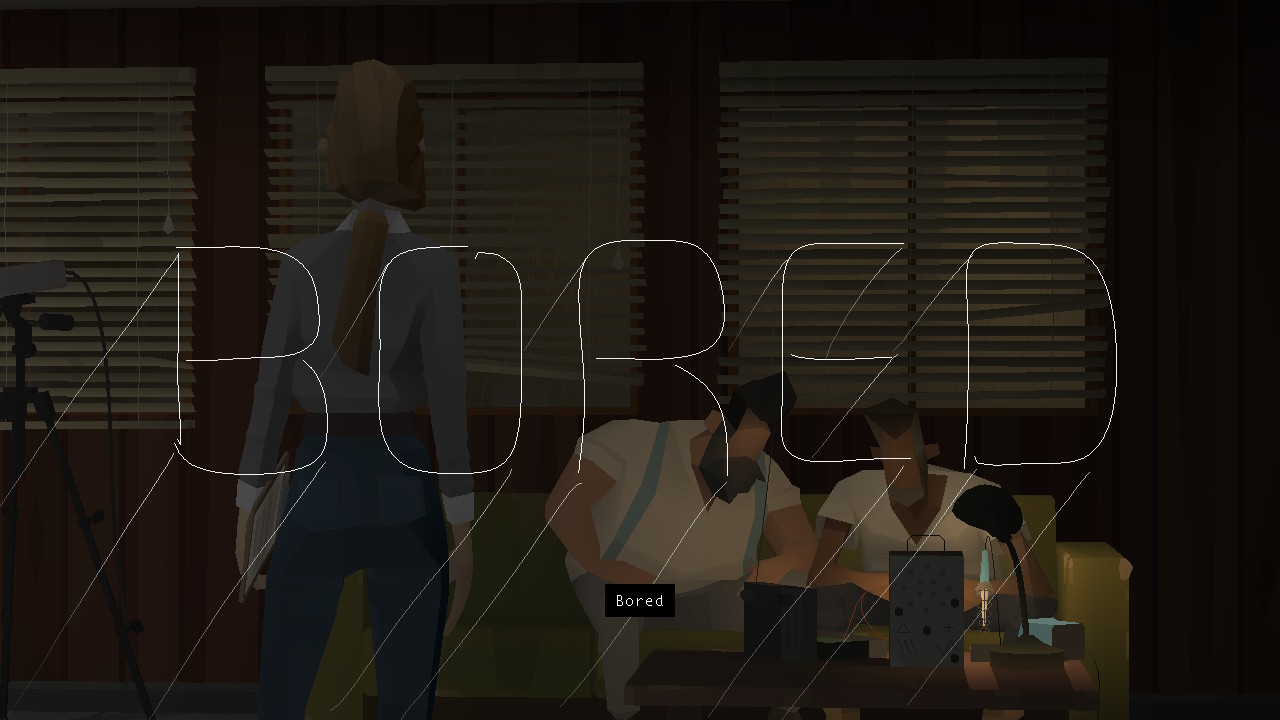

Both these sounds exist in a passive space separate from the active listening Emily may participate in by directly interacting with a person or object. The sounds are mixed into the soundscape by turning the camera in their direction and it is here that we return to the subject of player control. The player can hold on these sounds for an indefinite amount of time, to absorb them and their presence in the atmosphere but there is no guarantee the player character, Emily, is experiencing them in the same way. This is compounded by the fact that if you idle long enough, the word ‘bored’ will appear inscribed across the screen, in the style that is common to the drawings that accompany Emily’s selection of the objects of the station. (figure 5)

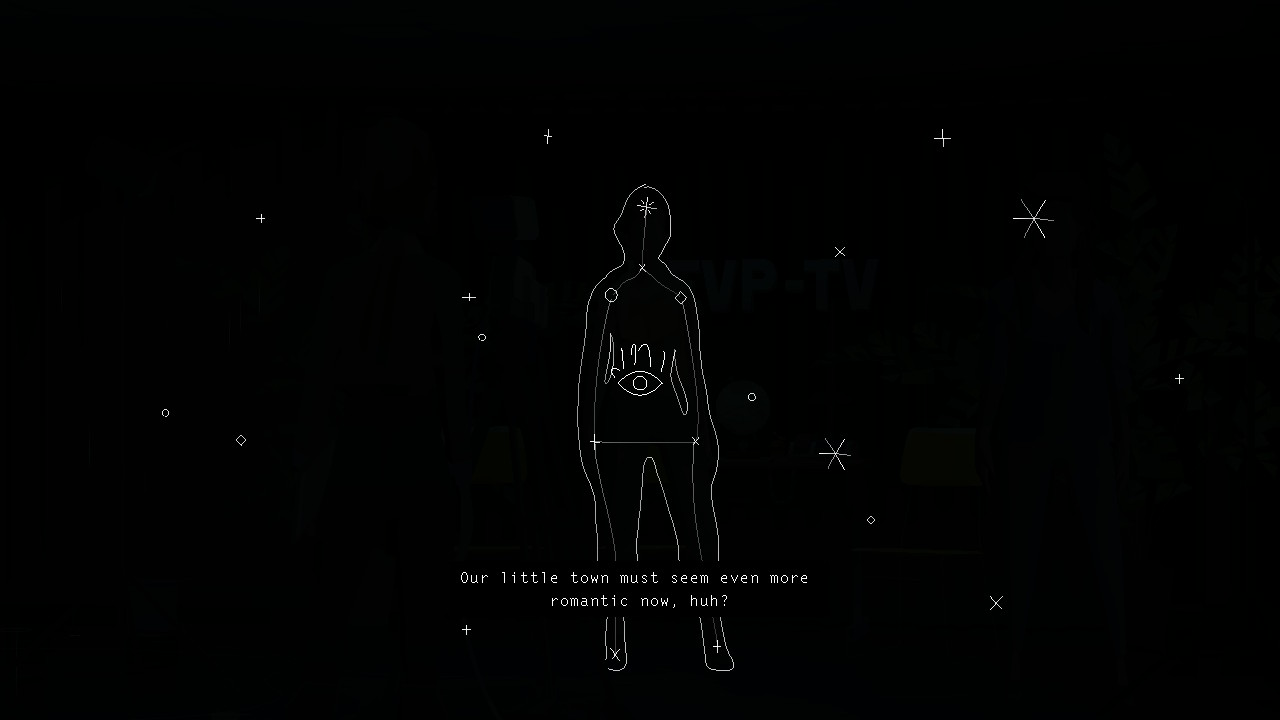

This manipulation of time is the most direct control the player is able to exert on the game and with this, the concept of the ‘ghost’ within the player-character relation is expressed. As I’ve explored earlier, the storm is presented as inevitable, so the process of observing is less an act of prevention than an act of lingering, of appreciating and understanding the space. Yet due the perceptive difference between the player and character, the control of only Emily’s thoughts and her independent reactions, the player functions like a ghost. They are a physically absent presence that influences but doesn’t control the characters present. But the game acts too acts as a ghost to the player, embedding them in a sensual experience and endearing them to the space. Like Emily experiences when the lights go out, the characters have already become embedded (figure 6), in a starlike space beyond the physical, and they may stay with player until they ‘decline peacefully into irrelevance.’

Bibliography

- Kentucky Route Zero TV Edition, developed by Carboard Computer, Publisher Annapurna (2020).

- Grace Benfell, ‘Video killed the video star: on ‘Un Pueble de Nada’ by Cardboard Computer, Radiator.

- Jessica Conditt, ‘This is the end of Kentucky Route Zero,’ engadget, 2020.

- Austin Walker, ‘Kentucky Route Zero Pays off on Nine Years of Hope and Doubt’, Waypoint 2020.

- Robert Yang, ‘At Home with the Ghosts: Kentucky Route Zero’s Reworking of Capitalist Space,’, Sidequest, 2020.